Meet David McKenna, Post Production and Scoring Stage Manager at UCLA’s School of Theatre, Film and Television.

We had the pleasure of talking to David about how he got started in the music industry, what led him to teach at UCLA and how loudness and dynamics in music have changed over the years.

Enjoy!

MeterPlugs: What sparked your interest in music recording?

David: As a kid, my two best friends were great guitarists and writers. I was neither, so I learned how to record them instead.

I started in 1992 with a 4-track tape machine that I’d bounce to two tracks and then back to the 4-track for additional overdubs, if needed. I learned that trick from Eddie Kramer who used a similar method working with Hendrix and The Beatles.

MP: Did you go to school for music recording?

David: I went to SF State where I learned from John Barsotti - who is kind of a legend in the Bay Area - earning my BA in Recording Engineering and my MA in Production. During that time I was the Production Manager for the college radio station KSFS, taught a few lab and seminar sections, and worked as an intern at several Bay Area recording studios.

MP: How did you get started in the industry after graduating?

David: In 2000, I moved back to LA where I eventually began working at Cherokee Studios, briefly as a 2nd, then Lead Technical Engineer and ultimately Lead Engineer. Most of my work was the typical set-up and tear down, albeit for some really cool artists (I’m not a fan of name dropping, but I’ll say that I did work on a few projects that earned, or were nominated for, GRAMMY’s).

A really important development for me was that I often assisted on mastering sessions at Capitol for the albums I had worked on. It was there that I met Ron McMaster and really got to pick his brain on how to master a song while still keeping the sonic character of the music. This was right at the time when the loudness wars were getting out of hand (although they would continue to do so), so it was great to get his perspective.

MP: What lead you to teaching?

David: Around 2005, I heard that Portland was going to be the “next Seattle” and that I needed to move up there right away to strike while the iron was hot. To say that Portland did not become the next Seattle would probably be a fair statement - I spent more time working on TV projects than music - so I briefly moved back to San Francisco and then ultimately back to Los Angeles where I have been since 2007.

By that time, many of the studios in LA had shuttered due to the collapse of the music industry, so to make ends meet I went into education. I’ve always enjoyed teaching, and it is a unique skill set that not everyone has. In 2009, I got a gig teaching music recording at UCLA as part of my job managing the Scoring Stage at the School of Film. I’ve been doing that ever since.

MP: Which classes do you teach?

David: We have a three-class curriculum that is centered on the basic pillars of tracking, editing and mixing:

The intro class is primarily designed to familiarize the students with the basic skills they need to not break our equipment.

The intermediate class starts to get into the nitty-gritty of more complex recording scenarios, more involved editing tools and a significant focus on how to mix while avoiding the common pitfalls often made in the process.

The advanced class is a partnership with Capitol Studios, where the students get to learn how they track, mix and master both a pop group as well as an orchestra.

MP: What do you teach your students about loudness and dynamics?

David: I have a lecture about preserving dynamics at the end of the intermediate class that is tied into the state of the music industry. I believe the two are in fact linked. Labels have been chasing this imaginary belief that louder songs are better and will result in sales (an oversimplification, but certainly a symptom). I hasten to add that I also have zero sympathy for the illegal downloaders who have irrevocably made music worse through their actions.

But even back in 2000 I was sensitive to how over-compression was ruining the sound and subsequent enjoyment of a number of albums. Recently, I bought an album that was mastered so loud that I threw it away after one painful listen, even though it was a famous band that I genuinely enjoyed in a live setting.

When I gave my first intermediate class in 2010, my mastering lecture was already in place. It was really very simple to construct:

I took a number of songs culled from Rolling Stone’s top 500 albums from the 1960s to the present day (or at least pretty recently). I’ve been buying CDs from a very early age, and a number of these releases were often pure digital “masters” made from the original tapes. It took several years before labels began “re-mastering” albums and adding unnecessary EQs and compression to try to sell to a newer generation of buyers. I avoided using those altered versions in my presentation.

My Pro Tools session has two progressions. The first progression is just me playing the songs - typically a few bars at a time - in sequence. I start with the first song at a moderate volume and say in a normal speaking voice the years of release, “1969… 1972… 1973… 1976… 1980…” By the time “1996” comes around, I have to raise my voice a bit to be heard over the louder music. Once I get to the mid 2000s I am shouting. And by the modern day, I am at a full scream to be able to be heard over the master. I then switch back to 1969 to return to sanity.

I then play my second sequence where I have taken all the songs and normalized them to an RMS of -20 dBFS so that they are all the same relative volume. Here I go back and forth from modern songs to older songs and tell the students, “Listen to the snare drum on these two… Listen to the bass guitar one these two… Listen to the vocals here…” In every case, older songs without the ridiculous amount of compression have a greater tonality and depth which is simply not present in modern mixes. It’s not even close.

MP: How have you incorporated Dynameter into your lecture?

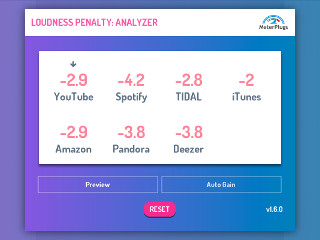

David: When I saw your YouTube video about Dynameter, I knew it would help serve to further demonstrate not only the point, but also give a strong counter argument to the popular perception that “louder = better.” If the websites and streaming services that people are hearing music on are already performing a similar volume adjustment like I do on my second sequence, we are only left with worse sounding music (and who wants to buy bad sounding music?).

I was amazed at just how effective your meter was at bolstering my argument. By applying Dynameter on every channel of my first progression of songs (it took two full computer monitors to open all of them simultaneously, which you can do in Pro Tools by simply holding down the Shift key in case your readers are not familiar with that little trick), there was an easy to see evolution where the mixes went from plump green, to yellow, to orange, to red, to brown, and ultimately ashen grey.

Top to bottom: Dynameter showing dynamics getting progressively worse

Top to bottom: Dynameter showing dynamics getting progressively worse

Given the way the meter populates the image, it was not too hard to add, “Not only do we hear these songs sounding like crap, but we can see that in addition to looking like crap with these brown mixes, but it has gotten into malnourished crap with these grey mixes.” Every student got it.

MP: Do dynamics have a chance? What do you think the future holds?

David: There is so much work that goes into getting a magical performance from a group of musicians. The musicians, engineers, and producer all have to be on this razor thin wire between success and failure.

When compression was used effectively (which based on my lecture went up to about the mid 90s), it could actually serve the music - not too dissimilar from the long pole that tightrope walkers use to keep their balance. After the loudness wars took off in earnest with the development of the iPod in 2001, that pole started to become more and more like a one-ton weight, dragging everything down. But because the human brain is wired to prefer loud sounds over quiet ones, that weight has gotten ever larger.

Back during the Salem witch trials, there was a man named Giles Corey who was “pressed” to death. He was forced to lie down on his back, with a large board placed over his body, and the executioners added boulder after boulder on top until he eventually succumbed to the pressure. Near the very end of his life, they had to shove his tongue back into his mouth with a stick. His last words were, “More weight.” I think of the loudness wars in a similar context. Our brain just keeps saying, “more weight,” all the way to the point that the music has in fact died.

I have a good friend who used to do extreme audio compression for in-flight movies on airplanes so the passenger can hear the whispered dialog over the sound of the jet engines on those horrible headphones. I asked him what his RMS was set to: -6 dBFS. There are songs today with an RMS of -6.5. That is just insane when you think of it. We have music done by professional musicians, engineers and producers that only has slightly more dynamic range than the worst possible listening environment on the planet.

My hope is that we are at the point in the industry in which the tongue is lolling out and the desire for ever louder mixes is about to die. At some point I can’t be the only person who is bothered about this. At some point, I’d think the musicians, engineers and producers would start to push back on this pressure to the preserve the magic they created.

I sincerely hope your Dynameter, coupled with your web-video that demonstrates why it is so important, will help move us back to the realm of sanity. I genuinely look forward to the day when the vast majority of the albums in the past 20 years (and the last 5 in particular) are either re-mastered to remove this awful over-compression, or even re-mixed to undo what a lot of engineers felt they needed to do in order to be “relevant” to the times: I honestly know of engineers who perform this aggressive compression on their output bus so as to deliberately cut out the job of the mastering engineer. Things cannot continue in this manner.

20 years ago I used to buy an album a week. Sometimes two. Now I buy maybe one a year because they are by and large un-listenable. This is not a statement about the quality of the music contained therein; it is purely about the lost tonality. If I knew that albums were being re-released with an RMS of at least -14 (I have to admit a preference for -18), that would prompt me to start buying again. I hope the public will too.